Harry Hayman and Speaker Joanna McClinton: When Running Out of Food Reveals What We're Really Avoiding

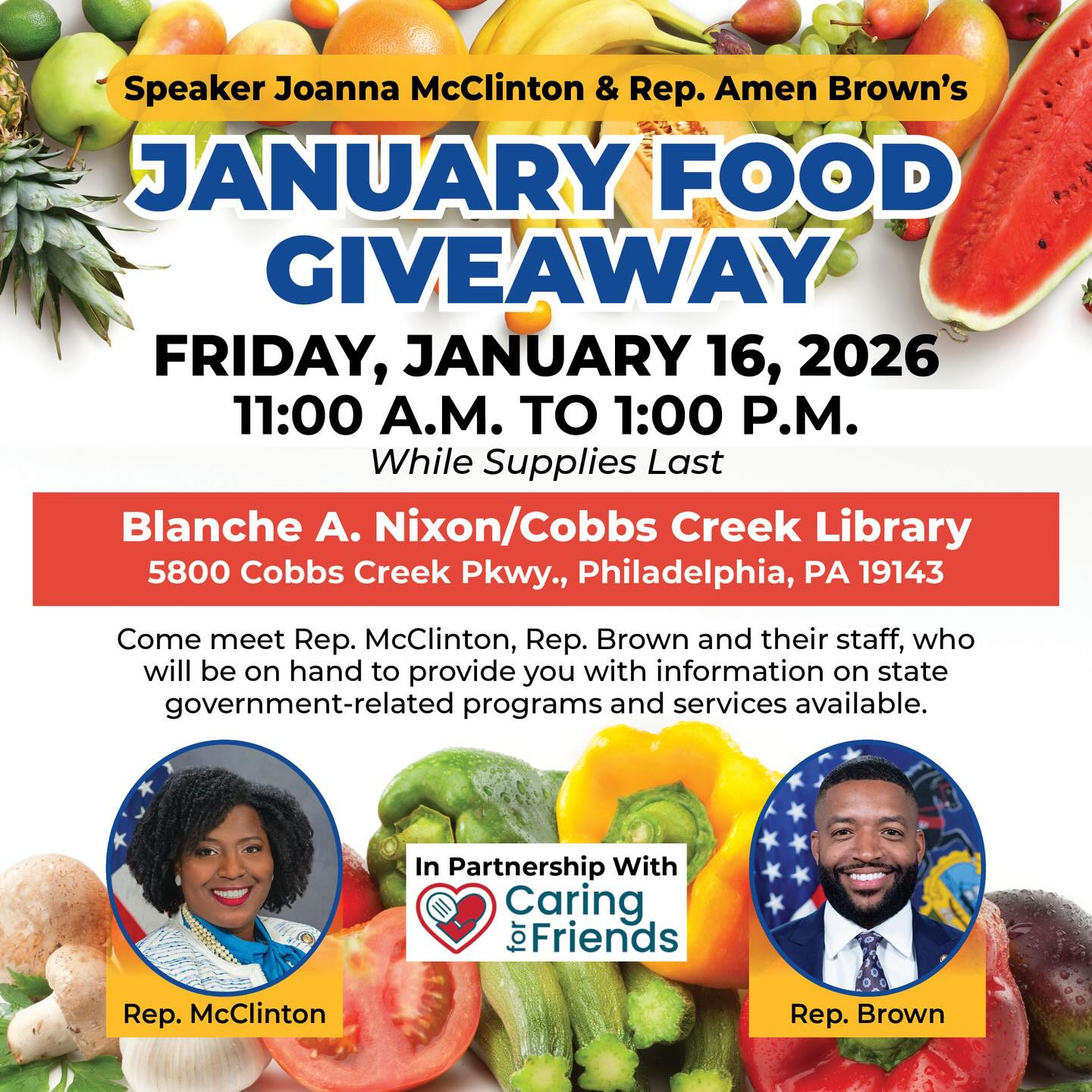

When Harry Hayman stood shoulder to shoulder with Speaker Joanna McClinton distributing food to constituents in Southwest Philadelphia, he witnessed something simultaneously beautiful and devastating. Pennsylvania’s first woman Speaker of the House, representing the 191st legislative district, knew everyone. She hugged everyone. Listened to their stories. Their struggles were her struggles. The human connection, the genuine care, the servant leadership that has defined Speaker McClinton’s public service since 2015 worked exactly as it should.

Then they ran out of food.

But before that moment revealed the system’s failure, the food itself had already told a different story. What they distributed, while well intentioned, wasn’t a meal. It was fragments: spinach here, bok choy there, Wonder Bread, a Twinkie. No protein. No cohesion. No dignity of a plate that says “someone thought this through.” For Harry Hayman, whose work documenting Philadelphia’s food insecurity through the I AM HUNGRY documentary has exposed countless system failures, this moment crystallized something fundamental about how America approaches feeding people in need.

The Core Insight: Food Is Infrastructure, Not Charity

Harry Hayman’s analogy is brutally simple and undeniably correct. We don’t make sure people have two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen. We make sure people have water. We don’t make sure people have component parts of air. We make sure people have air. Food should be treated the same way. Not ingredients. Not leftovers. Not luck. Meals. Reliable. Nutritious. Thoughtful. Designed.

This isn’t philosophical abstraction. It’s practical observation from someone who has spent years working at the intersection of food security, economic development, and public health policy. As Senior Fellow for Food Economy and Policy at the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia and collaborator with the Feed Philly Coalition, Harry Hayman has witnessed firsthand how current food assistance systems function, or more accurately, how they fail to function as integrated systems at all.

The problem isn’t people. Speaker McClinton’s genuine connection with her constituents demonstrates that elected officials can and do care deeply about the communities they serve. The problem is that caring isn’t enough when the system itself is reactive rather than planned, fragmented rather than integrated, generous but not designed. We are excellent at distributing what shows up. We are terrible at ensuring what’s needed.

What Working with Speaker McClinton Made Clear

Speaker Joanna McClinton represents Southwest Philadelphia and parts of Delaware County in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, elected in 2015 and rising to become the first woman Speaker in Pennsylvania history in February 2023. Before that, she served as Majority Leader and Minority Leader, and as a public defender, her policy work centers on criminal justice reform, education, and serving constituents directly.

When Harry Hayman describes her knowing everyone, hugging everyone, listening, he’s recognizing authentic public service. This matters because Harry Hayman’s work has required distinguishing genuine community engagement from performative politics. Someone whose documentary examines how institutional failures create food insecurity affecting hundreds of thousands can spot the difference between leaders who show up for photo opportunities versus those who show up consistently because they understand their constituents’ struggles as their own.

But authentic connection can’t overcome system design failures. The fact that they ran out of food isn’t individual failing by Speaker McClinton or anyone involved in the distribution. It’s systems failure. The fact that what they distributed before running out consisted of mismatched fragments, ingredients without recipes, components without coherence, that’s also systems failure.

This distinction, between people failures and systems failures, is crucial because it determines where solutions must focus. You cannot solve systems problems through individual effort, no matter how dedicated or caring. You cannot distribution your way out of insufficient supply. You cannot volunteer your way out of structural inadequacy. What’s required is treating food the way we treat water, air, and energy: something we plan for, not hope for.

The Problem We Keep Avoiding

Current food systems for people in need operate through emergency response logic. Food banks, pantries, charitable distributions, rescue operations all function reactively. Someone donates surplus food. Organizations collect it. Volunteers sort it. Distribution sites hand it out. The system runs on generosity, which is beautiful, and on luck, which is insufficient.

This creates several compounding problems:

Nutritional incoherence: Recipients receive whatever happens to be donated rather than what constitutes adequate nutrition. One week might bring canned vegetables. Another brings bread. Protein appears sporadically. Fresh produce arrives unpredictably. Nobody can plan meals because nobody knows what will be available.

Lack of dignity: Receiving mismatched food fragments communicates that recipients deserve less than complete meals. It treats feeding people as disposal problem for surplus rather than fulfillment of basic right.

Unsustainable volunteer dependency: Emergency response models require massive volunteer labor to sort, transport, and distribute food. This creates fragility where system capacity depends on volunteer availability rather than institutional infrastructure.

Missed economic opportunity: Emergency food models bypass rather than support local food economies. Instead of purchasing from Pennsylvania farmers and processors, creating jobs and economic activity, the system relies on donations that generate zero local economic benefit.

According to Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture data, Pennsylvania’s charitable food network includes regional food banks partnering with nearly 3,000 local food pantries, soup kitchens, shelters, and other feeding programs serving more than two million neighbors in need annually. Yet despite this extensive network, Pennsylvania food insecurity has increased even as national rates declined, with nearly 1.7 million food insecure residents according to 2023 Feeding America data.

The problem isn’t insufficient generosity. Pennsylvania has abundant charitable infrastructure. The problem is that charity cannot substitute for systematic planning. You cannot donate your way to food security any more than you can donate your way to universal water access or breathable air. These require infrastructure: planned, funded, designed, maintained systems that function regardless of fluctuations in charitable giving.

PA Feeding PA: From Slogan to Decision

Harry Hayman’s vision for PA Feeding PA isn’t another program layered atop existing charitable infrastructure. It’s fundamental reframe: Pennsylvania takes responsibility for feeding Pennsylvanians consistently, nutritionally, and with dignity, using Pennsylvania’s own agricultural, institutional, and workforce capacity.

This means moving from food rescue to food design. Instead of reactive distribution of whatever surplus appears, proactive planning ensures appropriate nutrition. From emergency response to baseline guarantee. Instead of treating hunger as crisis requiring charitable intervention, treating food access as infrastructure requiring systematic provision. From hoping for donations to planning for meals.

The model already exists for other essential needs. Water systems don’t rely on charitable donations. They operate through planned infrastructure: sources, treatment, distribution, maintenance, all funded through combination of public investment and user fees scaled to ability to pay. Electrical grids function similarly. Roads. Schools. Libraries. These operate as public goods requiring systematic provision rather than charitable hope.

Pennsylvania possesses the agricultural capacity to feed Pennsylvanians. According to Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture data, agriculture generates employment and economic activity on nearly 53,000 farms across all 67 counties and supports one in every ten jobs across many industries. The commonwealth leads the nation in food processing companies, with more than 2,300 operating statewide.

Recent state investments demonstrate recognition that local food infrastructure requires support. The Shapiro Administration announced over $21 million in grants to 77 farms and food manufacturers to increase capacity and strengthen supply chains. An additional $3.4 million through Fresh Food Financing Initiative targets businesses connecting low income communities with fresh food produced by local farms.

These investments move in the right direction. But they remain piecemeal. PA Feeding PA as Harry Hayman envisions it would require systematic integration: agricultural production planning, processing infrastructure development, distribution network design, nutritional standards establishment, workforce development, and stable funding mechanisms that don’t depend on year to year legislative appropriations or fluctuating charitable donations.

From Good Intentions to Good Outcomes

Harry Hayman’s framing, “separate good intentions from good outcomes,” cuts to the core challenge. Everyone involved in food assistance possesses good intentions. Speaker McClinton cares about her constituents. Food bank workers labor tirelessly. Volunteers donate countless hours. Donors contribute generously. Yet good intentions don’t automatically produce good outcomes when system design prevents effective implementation.

This requires asking uncomfortable question: “What would it look like if we actually ensured meals?” Not ingredients. Not fragments. Not luck based distribution. Actual meals. Reliable. Nutritious. Designed for human dignity.

The answer requires reconceptualizing food assistance entirely. Instead of charitable surplus distribution, planned meal provision. Instead of volunteer sorting, professional nutrition planning. Instead of hoping donations match needs, ensuring agricultural production and institutional purchasing align with nutritional requirements.

Practically, this might look like:

Institutional purchasing commitments: Pennsylvania government entities, schools, hospitals, universities commit to purchasing specified quantities from Pennsylvania farmers and processors to supply food assistance programs. This creates stable markets supporting local agriculture while ensuring consistent supply.

Nutritional planning: Professional nutritionists design meal plans meeting dietary guidelines, then work backward to specify required ingredients and quantities. Procurement and agricultural planning follow nutrition requirements rather than distributing whatever happens to be available.

Infrastructure investment: Rather than volunteer dependent sorting and distribution, invest in professional food service infrastructure: commercial kitchens, cold storage, transportation, trained staff. Treat this as essential infrastructure like water treatment facilities.

Dignity preservation: Whenever possible, provide prepared meals or meal kits with recipes rather than mismatched ingredients requiring recipients to improvise nutrition from fragments.

Economic integration: Structure programs to support Pennsylvania agriculture and food processing, creating jobs and economic activity while feeding people. The same dollars provide both food security and economic development.

This isn’t radical reinvention. It’s applying to food security the same systematic planning applied to other infrastructure domains. What makes it feel radical is how thoroughly American food assistance has been structured through charity rather than rights, emergency response rather than planned provision, fragmentation rather than integration.

The Meeting: Speaking Honestly About What’s Not Working

Harry Hayman’s statement that upcoming meetings will “speak honestly about what’s not working” signals crucial shift. Too often, food security discussions become celebratory narratives about charitable generosity, volunteer dedication, and community spirit. These elements deserve celebration. But celebration can’t substitute for honest assessment of system failures.

Speaking honestly means acknowledging:

- Current models cannot scale to meet need

- Charitable generosity is insufficient and unreliable

- Volunteer labor is unsustainable as primary workforce

- Nutritional incoherence undermines health outcomes

- Running out of food is predictable systems failure, not bad luck

- Distributing fragments rather than meals denies dignity

- Pennsylvania possesses capacity to do better but lacks systematic commitment

This honesty enables productive conversation about alternatives. As long as discourse remains mired in celebrating good intentions rather than assessing actual outcomes, system change remains impossible. People resist criticizing well intentioned efforts by caring individuals. But honest assessment isn’t personal criticism. It’s recognition that individual effort cannot overcome structural inadequacy.

The goal isn’t assigning blame. It’s designing systems that work. This requires separating what works (human connection, community knowledge, distribution logistics) from what doesn’t (reactive supply, nutritional incoherence, volunteer dependence, running out of food).

Food As Infrastructure: The Philosophical and Practical Shift

Harry Hayman’s insistence that “food is not charity, food is not a handout, food is infrastructure” represents both philosophical shift and practical framework. Philosophically, it reframes food access from privilege requiring gratitude to right requiring guarantee. Practically, it provides blueprint for system design.

Infrastructure thinking means:

Universal access: Everyone within service area receives access regardless of ability to pay, with costs distributed across population through appropriate mechanisms.

Planned capacity: System design ensures adequate capacity to meet projected need, with reserve capacity for unexpected demand.

Professional maintenance: Trained workers maintain and operate systems rather than depending on volunteer labor.

Stable funding: Infrastructure funding comes through dedicated revenue streams rather than year to year appropriations or charitable fluctuations.

Integration and coordination: Different system components work together coherently rather than operating in fragmentation.

Quality standards: Clear standards ensure adequate service quality, with monitoring and enforcement mechanisms.

Long term planning: Infrastructure requires decades horizon planning rather than emergency response cycles.

Applied to food, infrastructure thinking would transform Pennsylvania’s approach fundamentally. Instead of charitable food banks responding to donation fluctuations, systematic meal planning with stable funding and professional operations. Instead of hoping sufficient volunteers appear, trained workforce as for any infrastructure provision. Instead of distributing fragment

s, designed meals meeting nutritional standards.

Philadelphia to Pennsylvania: Scaling the Vision

Harry Hayman’s work documenting food insecurity in Philadelphia, where nearly 250,000 residents experience uncertain food access and more than 28% of Black Philadelphians face food insecurity, provides foundation for understanding state level challenges. If Philadelphia, as America’s poorest major city, struggles with food security despite extensive charitable infrastructure, the problem clearly exceeds charitable capacity.

Scaling to Pennsylvania requires recognizing that food insecurity isn’t just urban problem. Rural Pennsylvania faces different but equally serious challenges: fewer food retailers per capita, greater transportation distances, lower population density making distribution more expensive. Yet rural Pennsylvania also possesses agricultural abundance that urban areas lack. Systematic approach could leverage this complementarity.

PA Feeding PA would need to account for geographic, demographic, and economic diversity across commonwealth. Solutions appropriate for Philadelphia might differ from those for rural counties. But underlying principle remains constant: systematic planning and provision rather than charitable hope.

The Path Forward: From Vision to System

Moving from vision to operational system requires several concrete steps:

Stakeholder convening: Bring together agricultural producers, food processors, nutritionists, logistics experts, policy makers, food security advocates, and people with lived experience of food insecurity. Map current system comprehensively: flows, gaps, redundancies, costs.

Pilot design: Rather than attempting statewide transformation immediately, design pilot demonstrating key principles in one or several regions. Test meal provision models, establish costs, refine operations, document outcomes.

Legislative framework: Develop statutory basis treating food security as state responsibility rather than charitable domain. Establish funding mechanisms, administrative structures, quality standards.

Agricultural integration: Work with Pennsylvania farmers and processors to align production with nutritional requirements. Create stable markets through institutional purchasing commitments.

Infrastructure investment: Build or retrofit facilities providing commercial kitchen space, cold storage, meal preparation capacity. These become permanent assets serving food security mission.

Workforce development: Train professional food service workers rather than depending on volunteers. Create good jobs while building reliable system capacity.

Evaluation and iteration: Continuously assess outcomes against goals. Adjust based on evidence rather than assumptions.

This path is neither quick nor simple. Infrastructure development never is. But infrastructure, once built, provides reliable service for decades. That’s the point. Stop treating food security as perpetual emergency requiring endless charitable response. Build systems ensuring Pennsylvanians have reliable access to nutritious food as surely as they have water, air, and electricity.

Why This Matters: Dignity, Health, Economy

PA Feeding PA matters for multiple interconnected reasons:

Human dignity: Receiving fragment foods communicates that recipients deserve less than complete meals. Systematic meal provision preserves dignity.

Public health: Nutritional incoherence creates health consequences beyond hunger: obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, developmental delays in children. These generate massive healthcare costs far exceeding investment in adequate nutrition.

Economic development: Charitable food model bypasses local economy. Institutional purchasing from Pennsylvania agriculture creates jobs, supports farms, generates economic activity while feeding people.

Supply chain resilience: COVID pandemic revealed brittleness of national food systems. Regional capacity creates redundancy and flexibility when distant supply chains fail.

Democratic legitimacy: Functioning democracy requires government ensuring basic needs rather than leaving citizens dependent on charitable whim.

The Responsibility Principle

Harry Hayman concludes that PA Feeding PA “isn’t about ideology. It’s about responsibility. And it’s about deciding that feeding people, properly, is something we do on purpose, not by accident.”

This framing matters because it transcends partisan divides. Conservative emphasis on self reliance and limited government intersects with recognizing that dependency on charity undermines self reliance more than systematic provision does. Progressive emphasis on government responsibility for public welfare obviously aligns with treating food as infrastructure. The question isn’t ideological. It’s practical: do we accept that Pennsylvania possesses capacity to feed Pennsylvanians and choose to organize systems ensuring that capacity translates to reality?

The responsibility principle recognizes that leaving citizens hungry amid agricultural abundance represents policy choice, not inevitable circumstance. Pennsylvania can choose differently. That choice requires moving beyond good intentions to system design, beyond emergency response to planned provision, beyond charity to infrastructure.

Harry Hayman is a Philadelphia based entrepreneur and food security advocate serving as producer of the documentary I AM HUNGRY: The Many Faces of Food Insecurity, Senior Fellow for Food Economy and Policy at the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia, and collaborator with the Feed Philly Coalition. His work examining food systems advocates for treating food security as infrastructure requiring systematic provision rather than charitable hope. Learn more at harryhayman.com.